ST JUST ORDINALIA

Cornish medieval mystery plays

Performed by the community

in the historic amphitheatre

St Just Plen-an-Gwari

About

The three Ordinalia plays are the oldest surviving trilogy of plays in Great Britain, comprising 'Creation of the World', the 'Passion of Christ', and the 'Resurrection of our Lord'. They were written by the clerics of Glasney College in Penryn, the best known and most important of Cornwall's religious institutions.

The Ordinalia plays are contemporary with the York and Wakefield cycle of Mystery plays, but they are a different genre with a different form of production. They were a trilogy of three separate plays designed to be performed by one community over a three day period. By contrast, the York and other Mystery plays are a cycle of 50 scenes, each designed to be performed by a separate craft -guild with its own interpretation and production methodology.

The Ordinalia plays were designed to be played in a round amphitheatre known as a Plen an Gwari (Playing Place) of which St Just has one of the two remaining operative ones. It is the oldest working amphitheatre in Great Britain.

The Ordinalia plays have three singular characteristics. Firstly, they not only present stories recorded in the Bible, but they also draw on apocryphal stories circulating at the time - such as the Harrowing of Hell, the Death of Pilate, and the Smith and the Nails.

Secondly, the original manuscript text includes 27 place-names in Cornwall, recording land-grants given to servants, mostly small hamlets near Penryn. In the Passion, the smith making the nails for Christ's cross is stated to work at Marazion, home to St Michael’s Mount, some 16 miles from Penryn!

And finally, the Ordinalia weaves the legend of the Holy Rood (see Student Resources area below) into the narrative, allowing each play to contain a number of interconnected stories. This motif does not play a significant part in other surviving English Mystery plays.

There are three surviving Ordinalia manuscripts - an original fifteenth century manuscript, held in the Bodleian Library Oxford, from which the other manuscripts appear to have been copied. A second text is in the Bodleian Library, and a third in the National Library of Wales.

In 1969 the Drama Department at Bristol University staged the Ordinalia plays for the first time in over 300 years at Perran Round in Perranporth - the other Cornish surviving Plen an Gwari.

In 2000, with a Millennium Festival grant, the St Just Ordinalia Company performed Origo Mundi.

In 2001, they performed The Passion, producing The Resurrection the following year.

In 2004, they uniquely performed the full cycle of Ordinalia plays.

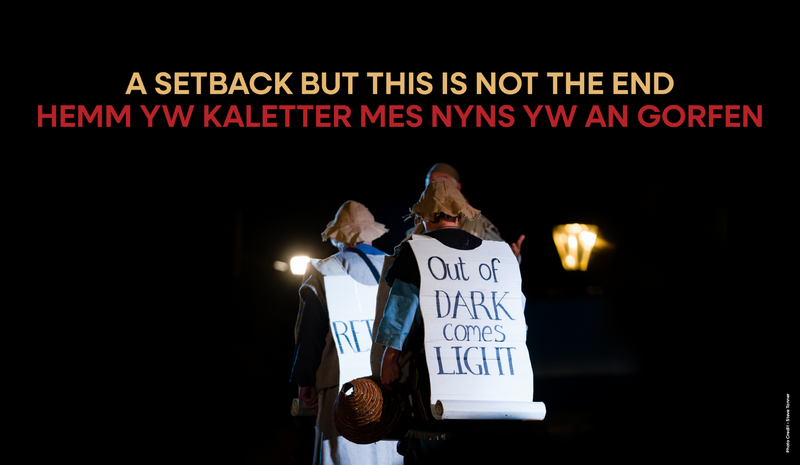

Seventeen years later, in September 2021 the Cornish Ordinalia plays were again performed in St Just - on this occasion all three plays being performed in repertory, a unique and spectacular experience. Audiences of over 5000 people heard the Cornish Language being sung and spoken, as they witnessed this amazing medieval piece of theatre being brought to life.

We're now working towards performing the St Just Ordinalia every 5 years, and we are currently fundraising to perform the plays again in September 2026.

The Ordinalia plays are contemporary with the York and Wakefield cycle of Mystery plays, but they are a different genre with a different form of production. They were a trilogy of three separate plays designed to be performed by one community over a three day period. By contrast, the York and other Mystery plays are a cycle of 50 scenes, each designed to be performed by a separate craft -guild with its own interpretation and production methodology.

The Ordinalia plays were designed to be played in a round amphitheatre known as a Plen an Gwari (Playing Place) of which St Just has one of the two remaining operative ones. It is the oldest working amphitheatre in Great Britain.

The Ordinalia plays have three singular characteristics. Firstly, they not only present stories recorded in the Bible, but they also draw on apocryphal stories circulating at the time - such as the Harrowing of Hell, the Death of Pilate, and the Smith and the Nails.

Secondly, the original manuscript text includes 27 place-names in Cornwall, recording land-grants given to servants, mostly small hamlets near Penryn. In the Passion, the smith making the nails for Christ's cross is stated to work at Marazion, home to St Michael’s Mount, some 16 miles from Penryn!

And finally, the Ordinalia weaves the legend of the Holy Rood (see Student Resources area below) into the narrative, allowing each play to contain a number of interconnected stories. This motif does not play a significant part in other surviving English Mystery plays.

There are three surviving Ordinalia manuscripts - an original fifteenth century manuscript, held in the Bodleian Library Oxford, from which the other manuscripts appear to have been copied. A second text is in the Bodleian Library, and a third in the National Library of Wales.

In 1969 the Drama Department at Bristol University staged the Ordinalia plays for the first time in over 300 years at Perran Round in Perranporth - the other Cornish surviving Plen an Gwari.

In 2000, with a Millennium Festival grant, the St Just Ordinalia Company performed Origo Mundi.

In 2001, they performed The Passion, producing The Resurrection the following year.

In 2004, they uniquely performed the full cycle of Ordinalia plays.

Seventeen years later, in September 2021 the Cornish Ordinalia plays were again performed in St Just - on this occasion all three plays being performed in repertory, a unique and spectacular experience. Audiences of over 5000 people heard the Cornish Language being sung and spoken, as they witnessed this amazing medieval piece of theatre being brought to life.

We're now working towards performing the St Just Ordinalia every 5 years, and we are currently fundraising to perform the plays again in September 2026.

Ordinalia 2021

A glimpse into the 2021 community production...

News

2021 Features

2021 Production

'A successful, major community event that could not fail to arouse intense admiration and not a little envy from any outsider' - Professor Sally Mackey, Royal Central School of Speech and Drama

'The spirit of St Just's Ordinalia should be bottled up and made available on the National Health'

Ted Lean, Project Director

At the Esedhvos Festival of Cornish Culture 2022, the Grand Bard’s award for outstanding achievement was presented to Producer Mary Ann Bloomfield for her work on the Ordinalia in St Just.

The St Just Ordinalia 2021 received a Glenda Hartland Award for seeking to promote active community involvement in Cornish cultural tradition, together with six Certificates of Recognition for Community and Creativity.

The cast of the 14th Century Ordinalia trilogy performances in September 2021 delivered, with spades, the aim of the original plays to impress the Christian bible stories on the local population. With creative, moving, dramatic, witty and farcical scenes adapted from the original by local playwright Pauline Sheppard, the actors performed at the top of their game.

Supported by a 34 strong choir led by Choir Director Vicky Abbott, who had written all new scores in Cornish for this 2021 production, and the 15 strong band led by Band Director Ben Sutcliffe the exquisite music emanating from beneath Heaven brought a depth and richness to the production. Over 150 costumes were needed for the three plays, designed with flair and originality by Meier Williams and pieced together by Bridget Gibbs, Sara Rose Whetherly and their team of sixteen. Eleven stages, 'Mansions' according to the original medieval texts, were designed by Graham Jobbins and built by his 27 strong team of set makers - the spectacular jaws of Hell unleashing fire and brimstone next to the grim Torturers' Mansion, and flanked by Pilate's palace.

Each of the 3 plays, had their own professional Director and Assistant Director - Oliver Gray and Isobel Bloomfield for Origo Mundi; Jason Squibb and Tori Cannell for The Passion; and Jennifer Fletcher and Kylie Skye Sullivan for The Resurrection. Jason Squibb was Artistic Director for all three plays, and Mary Ann Bloomfield was Producer.

This wide range of action involved some deft footwork from the technical crew - Vicki Cox as Production Manager supported by Nicky Wood as Stage Manager; Ethan Kent as Lighting Designer (with Lucy Gaskell in support), Millstone Sound's team of George and Tom; and the ever smiling Box Office presence of Kate Stebbing-Allen.

The contribution of the St Just community to this extraordinary celebration of Cornish heritage and culture cannot be underestimated. Over 245 volunteers came forward and helped make the 15 performances over a 2-week period an absolute triumph. And despite a few brief soggy moments, the moon and starlit autumn skies added a dramatic backdrop to the subject matter of the plays. The final moments of The Resurrection on the last night will stay in the minds and memories of the audience for years to come, especially the saxophone solo in Heaven.

The Ordinalia plays, although similar to the mystery plays of the North of England, are unique to Cornwall and an important part of the heritage of St Just in Pendeen, and the far South West.

They are the oldest surviving trilogy of theatrical plays in Britain.

St Just's Plen an Gwari is one of the two oldest working open air theatre spaces in Britain.

All photos of the 2021 productions used on this site were taken by Mike Newman and Steve Tanner

Ordinalia by Numbers

Over 6 centuries since written

3 surviving Ordinalia manuscripts

3rd staging of the plays in over 300 years

In 2021, 5 performances of each of the 3 plays.

2 surviving Plen an Gwaris from over 50 in Cornwall

248 Community volunteers. Total audience 5,875

Sponsors and Supporters

The St Just Ordinalia is a project organised by St Just and District Trust CIO. The charity was founded in 1997, and became a Charitable Incorporated Organisation in 2016.

As a community initiative, our project has been supported by the Mayor and Deputy Mayor of St Just Town Council, by the creative faculties at Falmouth University, and by the talented actors, singers, makers, musicians and volunteers of St Just (and Cornwall).

Our bids for St Just Ordinalia 2026 are currently supported by St Aubyn Estates and Cornwall Council.

St Just Ordinalia 2021 was supported by Sir Mark Rylance, actor, theatre director and playwright; Emma Rice, actress, director and theatre professional; Sir Michael Eavis CBE, creator of Glastonbury Festival; and among others, by the organisations listed below.

Past Productions

Origo Mundi - 'The Creation of the World'

September 2000

The Passion

August and September 2001

The Resurrection

August and September 2002

The Ordinalia Full Cycle

August 2004

Origo Mundi, The Passion, The Resurrection

September 2021

Student resources area

Discussion Topics and Ordinalia Bibliography

DISCUSSION TOPICS

The relationship of the Ordinalia plays to the Breton and German Mystery play traditions.

How the classical Greek and Roman play forms came to be introduced into medieval English literature.

The differences in style and content between the Cornish Ordinalia Mystery plays and the York, Chester and Wakefield Mystery Plays.

The influences affecting the author's choice of subject matter for the Ordinalia plays.

The use of English and Latin in medieval Cornish drama, and the reversal of roles in modern interpretations.

The novelty of the 'Ordinary' role in the Ordinalia trilogy.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

The Ordinalia Texts

CHUBB, Ray; JENKIN, Richard & SANDERCOCK, Graham (eds.) of NANCE, R. Morton & SMITH, A.S.D., The Cornish Ordinalia, first play: Origo Mundi (Redruth, Agan Tavas, 2001)

HARRIS, Markham, The Cornish Ordinalia. A Medieval Dramatic Trilogy (Washington: Catholic University of America Press, 1969).

KENT, Alan M, Ordinalia - The Cornish Mystery Play Cycle - A verse translation (London: Francis Boutle Publishers, 2005) with an informative introduction by Professor Brian Murdoch, University of Sterling.

NANCE, R. Morton & SMITH, A.S.D, The Cornish Ordinalia, ed. SANDERCOCK, Graham (3 vols. n.p.: Kesva an Tavas Kernewek/Cornish Language Board, 1982-1989).

NORRIS, Edwin, The Ancient Cornish Drama (2 vols. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1859; repr. London & New York: Blom, 1968). Full text here - Volume 1, Volume 2.

Studies of the Ordinalia

BAKERE, Jane A, The Cornish Ordinalia. A Critical Study (Cardiff, University of Wales Press, 1980).

BETCHER, G.J., 'A Reassessment of the Date and Provenance of the Cornish Ordinalia. Comparative Drama, 29 (1995-96), pp.436-453.

CRAWFORD, T.D., 'The Composition of the Cornish Ordinalia', Old Cornwall, 9 (1979-85), pp.145-153; 166-67.

CROSS, Sally Joyce, 'Torturers and Tricksters in the Cornish Ordinalia', Neuphilogische Mitteilungen, 84 (1983), pp.448-53.

DENNY, Neville, 'Arena Staging and Dramatic Quality in the Cornish Passion Play'. In his Medieval Drama: Stratford-upon- Avon Studies 16, pp.125-53.

FOWLER, David C., 'The Date of the Cornish Ordinalia', Medieval Studies, 23 (1961), pp.9-125.

FUDGE, Crysten, 'Aspects of Form in the Cornish Ordinalia with Special Reference to Origo Mundi', Old Cornwall, 8 (1973-79), pp.457-64; 491-98.

HALL, Jim, 'Maximilla, the Cornish Montanist: The final scenes of Origo Mundi', Cornish Studies, 7 (July, 1999).

HAWKE, Andrew, 'A Lost Manuscript of the Cornish Ordinalia', Cornish Studies, 7 (1979), pp.45-60.

KENT, Alan M, 'Out of the Ordinalia' published by Lyonesse, Cornwall, 1995

LONGSWORTH, Robert, The Cornish Ordinalia: Religion and Dramaturgy (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1967).

MARX, C.W., 'The Problems of the Doctrine of the Redemption in the ME Mystery Plays and the Cornish Ordinalia', Medium Aevum, 64 (1985), pp.20-32.

MEYER, Robert T., 'The Liturgical Background of Mediaeval Cornish Drama', Trivium, 3 (1968), pp.45-58.

MURDOCH, Brian, 'The Mors Pilati' in the Cornish Resurrexio Domini', Celtica 23 (1999), pp. 211-226, 1999.

MURDOCH, Brian, 'The Place-Names in the Cornish Passio Christi', Bulletin of the Board of Celtic Studies, 37 (1990), pp.116-8.

RODDY, Kevin, 'Revival of the Cornish Mystery Plays in St. Piran's "round" & of the York Cycle, 1969', New Theatre Magazine, 1969. No. 3, pp.6-19.

The website ‘Bibliography of Cornish Medieval Drama’, prepared by Sydney Higgens has additional information on Cornish Miracle and Mystery plays and other Cornish medieval drama.

The relationship of the Ordinalia plays to the Breton and German Mystery play traditions.

How the classical Greek and Roman play forms came to be introduced into medieval English literature.

The differences in style and content between the Cornish Ordinalia Mystery plays and the York, Chester and Wakefield Mystery Plays.

The influences affecting the author's choice of subject matter for the Ordinalia plays.

The use of English and Latin in medieval Cornish drama, and the reversal of roles in modern interpretations.

The novelty of the 'Ordinary' role in the Ordinalia trilogy.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

The Ordinalia Texts

CHUBB, Ray; JENKIN, Richard & SANDERCOCK, Graham (eds.) of NANCE, R. Morton & SMITH, A.S.D., The Cornish Ordinalia, first play: Origo Mundi (Redruth, Agan Tavas, 2001)

HARRIS, Markham, The Cornish Ordinalia. A Medieval Dramatic Trilogy (Washington: Catholic University of America Press, 1969).

KENT, Alan M, Ordinalia - The Cornish Mystery Play Cycle - A verse translation (London: Francis Boutle Publishers, 2005) with an informative introduction by Professor Brian Murdoch, University of Sterling.

NANCE, R. Morton & SMITH, A.S.D, The Cornish Ordinalia, ed. SANDERCOCK, Graham (3 vols. n.p.: Kesva an Tavas Kernewek/Cornish Language Board, 1982-1989).

NORRIS, Edwin, The Ancient Cornish Drama (2 vols. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1859; repr. London & New York: Blom, 1968). Full text here - Volume 1, Volume 2.

Studies of the Ordinalia

BAKERE, Jane A, The Cornish Ordinalia. A Critical Study (Cardiff, University of Wales Press, 1980).

BETCHER, G.J., 'A Reassessment of the Date and Provenance of the Cornish Ordinalia. Comparative Drama, 29 (1995-96), pp.436-453.

CRAWFORD, T.D., 'The Composition of the Cornish Ordinalia', Old Cornwall, 9 (1979-85), pp.145-153; 166-67.

CROSS, Sally Joyce, 'Torturers and Tricksters in the Cornish Ordinalia', Neuphilogische Mitteilungen, 84 (1983), pp.448-53.

DENNY, Neville, 'Arena Staging and Dramatic Quality in the Cornish Passion Play'. In his Medieval Drama: Stratford-upon- Avon Studies 16, pp.125-53.

FOWLER, David C., 'The Date of the Cornish Ordinalia', Medieval Studies, 23 (1961), pp.9-125.

FUDGE, Crysten, 'Aspects of Form in the Cornish Ordinalia with Special Reference to Origo Mundi', Old Cornwall, 8 (1973-79), pp.457-64; 491-98.

HALL, Jim, 'Maximilla, the Cornish Montanist: The final scenes of Origo Mundi', Cornish Studies, 7 (July, 1999).

HAWKE, Andrew, 'A Lost Manuscript of the Cornish Ordinalia', Cornish Studies, 7 (1979), pp.45-60.

KENT, Alan M, 'Out of the Ordinalia' published by Lyonesse, Cornwall, 1995

LONGSWORTH, Robert, The Cornish Ordinalia: Religion and Dramaturgy (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1967).

MARX, C.W., 'The Problems of the Doctrine of the Redemption in the ME Mystery Plays and the Cornish Ordinalia', Medium Aevum, 64 (1985), pp.20-32.

MEYER, Robert T., 'The Liturgical Background of Mediaeval Cornish Drama', Trivium, 3 (1968), pp.45-58.

MURDOCH, Brian, 'The Mors Pilati' in the Cornish Resurrexio Domini', Celtica 23 (1999), pp. 211-226, 1999.

MURDOCH, Brian, 'The Place-Names in the Cornish Passio Christi', Bulletin of the Board of Celtic Studies, 37 (1990), pp.116-8.

RODDY, Kevin, 'Revival of the Cornish Mystery Plays in St. Piran's "round" & of the York Cycle, 1969', New Theatre Magazine, 1969. No. 3, pp.6-19.

The website ‘Bibliography of Cornish Medieval Drama’, prepared by Sydney Higgens has additional information on Cornish Miracle and Mystery plays and other Cornish medieval drama.

The Bodleian library manuscript and online palaeography tutorial

Bodleian Library link to the manuscript of the original Ordinalia plays

The National Archive in Kew, London in conjunction with University College London have prepared an online tutorial into the reading of old handwriting in manuscripts, which can be accessed here.

The National Archive in Kew, London in conjunction with University College London have prepared an online tutorial into the reading of old handwriting in manuscripts, which can be accessed here.

The History of the Ordinalia Plays

The three Ordinalia plays are known to have been written by the clerics of Glasney College in Penryn, under the control of the Bishop of Exeter who in 1336 dedicated St Just Parish Church after its extensive rebuilding. Founded in 1265, Glasney College is probably the best known and most important of Cornwall's religious institutions, relying for its income on the rectoral tithes of many parishes, including St Just in Penwith.

Secular colleges such as Glasney fall short of the concept of medieval universities, but made considerable contributions to the religious, political, intellectual, educational, charitable, musical and artistic life of the time.

The Ordinalia plays were written in the late fourteenth century, and probably predate the York and Wakefield cycle of mystery plays, in that they are a different genre with a different form of production. The Mystery Plays were all written as a means of bringing the stories of the bible to the common people in their vernacular tongue - the language of Church services at that time being Latin. However, the Ordinalia plays were a trilogy of three separate plays designed to be performed by one community over a three day period. By contrast, the York and other Mystery plays are a cycle of 50 scenes, each designed to be performed by a separate craft -guild with its own interpretation and production methodology.

It is ironic that the Ordinalia plays, which were written medieval Cornish to introduce bible stories to the community in their mother tongue, should now be performed to introduce elements of the Cornish language to the English speaking community through the telling of bible stories. More so, since the occasional use of the English language in certain of the original medieval scenes is contrasted with the occasional use of the Cornish language in our modern productions.

The Ordinalia plays were also designed to be played in a round amphitheatre known as a Plen a Gwari - not paraded around the streets as in York. Action within the plays shifted around the arena, and more closely resembled the German medieval religious drama concept of ‘simultaneous staging’ (Simultanbühne). Uniquely, the Ordinalia plays have full stage directions in Latin, with an indication of sets, props and how action is to be performed - not unlike in theatre today.

The Ordinalia plays have three other other singular characteristics. Firstly, they not only present stories recorded in the Bible, but they also draw on apocryphal stories circulating at the time - such as the Harrowing of Hell, the Death of Pilate, and the Smith and the Nails. Secondly, the original manuscript text includes 27 place-names in Cornwall, particularly as land-grants given to servants, mostly minor ones near Penryn. In the Passion, the smith making the nails for Christ's cross is stated to work at Marazion, home to St Michael’s Mount, some 16 miles from Penryn!

And finally, the Ordinalia weaves the legend of the Holy Rood into the narrative, allowing each day's play to contain a number of interconnected stories. This motif, which is found in some Continental plays, does not play a significant part in other surviving English Mystery plays.

Scholars have found more parallel between the Ordinalia and the French religious tradition, than with the York Mystery plays. This tradition is exemplified by the fifteenth century Mystère de la Passion - which, like the Ordinalia, has an Old Testament Section (albeit relatively brief) followed by the main events in Jesus’ life (including the nativity, which is not in the Ordinalia).

There are three surviving Ordinalia manuscripts. There is the original fifteenth century manuscript, currently held in the Bodleian lLibrary Oxford, from which the other manuscripts appear to have been copied. There is a second text in the Bodleian Library, and a third in the National Library of Wales as part of the bequest of Sir John Williams, Bart., of Llansteffan, Carmarthenshire - a Welsh physician, who attended Queen Victoria.

In 1969 the Drama Department at Bristol University staged the Ordinalia plays for the first time in over 300 years at Perran Round in Perranporth - the other Cornish surviving Plen an Gwari besides that in St Just. In 1979 the Miracle Theatre Group performed The Beginning of the World, an Ordinalia adaptation, in Perran Round. In the year 2000, with a Millennium Festival grant, the St Just Ordinalia Company performed Origo Mundi; and in 2001, they performed The Passion, producing The Resurrection the following year. And in 2004, they uniquely performed the full cycle of Ordinalia plays.

Seventeen years later, in September 2021 the Cornish Ordinalia plays were again performed in St Just - on this occasion all three plays being performed in repertory, a unique and spectacular experience. And for the first time in over 300 years, the original mediaeval Cornish text was heard on stage in the part of doubting Thomas.

Secular colleges such as Glasney fall short of the concept of medieval universities, but made considerable contributions to the religious, political, intellectual, educational, charitable, musical and artistic life of the time.

The Ordinalia plays were written in the late fourteenth century, and probably predate the York and Wakefield cycle of mystery plays, in that they are a different genre with a different form of production. The Mystery Plays were all written as a means of bringing the stories of the bible to the common people in their vernacular tongue - the language of Church services at that time being Latin. However, the Ordinalia plays were a trilogy of three separate plays designed to be performed by one community over a three day period. By contrast, the York and other Mystery plays are a cycle of 50 scenes, each designed to be performed by a separate craft -guild with its own interpretation and production methodology.

It is ironic that the Ordinalia plays, which were written medieval Cornish to introduce bible stories to the community in their mother tongue, should now be performed to introduce elements of the Cornish language to the English speaking community through the telling of bible stories. More so, since the occasional use of the English language in certain of the original medieval scenes is contrasted with the occasional use of the Cornish language in our modern productions.

The Ordinalia plays were also designed to be played in a round amphitheatre known as a Plen a Gwari - not paraded around the streets as in York. Action within the plays shifted around the arena, and more closely resembled the German medieval religious drama concept of ‘simultaneous staging’ (Simultanbühne). Uniquely, the Ordinalia plays have full stage directions in Latin, with an indication of sets, props and how action is to be performed - not unlike in theatre today.

The Ordinalia plays have three other other singular characteristics. Firstly, they not only present stories recorded in the Bible, but they also draw on apocryphal stories circulating at the time - such as the Harrowing of Hell, the Death of Pilate, and the Smith and the Nails. Secondly, the original manuscript text includes 27 place-names in Cornwall, particularly as land-grants given to servants, mostly minor ones near Penryn. In the Passion, the smith making the nails for Christ's cross is stated to work at Marazion, home to St Michael’s Mount, some 16 miles from Penryn!

And finally, the Ordinalia weaves the legend of the Holy Rood into the narrative, allowing each day's play to contain a number of interconnected stories. This motif, which is found in some Continental plays, does not play a significant part in other surviving English Mystery plays.

Scholars have found more parallel between the Ordinalia and the French religious tradition, than with the York Mystery plays. This tradition is exemplified by the fifteenth century Mystère de la Passion - which, like the Ordinalia, has an Old Testament Section (albeit relatively brief) followed by the main events in Jesus’ life (including the nativity, which is not in the Ordinalia).

There are three surviving Ordinalia manuscripts. There is the original fifteenth century manuscript, currently held in the Bodleian lLibrary Oxford, from which the other manuscripts appear to have been copied. There is a second text in the Bodleian Library, and a third in the National Library of Wales as part of the bequest of Sir John Williams, Bart., of Llansteffan, Carmarthenshire - a Welsh physician, who attended Queen Victoria.

In 1969 the Drama Department at Bristol University staged the Ordinalia plays for the first time in over 300 years at Perran Round in Perranporth - the other Cornish surviving Plen an Gwari besides that in St Just. In 1979 the Miracle Theatre Group performed The Beginning of the World, an Ordinalia adaptation, in Perran Round. In the year 2000, with a Millennium Festival grant, the St Just Ordinalia Company performed Origo Mundi; and in 2001, they performed The Passion, producing The Resurrection the following year. And in 2004, they uniquely performed the full cycle of Ordinalia plays.

Seventeen years later, in September 2021 the Cornish Ordinalia plays were again performed in St Just - on this occasion all three plays being performed in repertory, a unique and spectacular experience. And for the first time in over 300 years, the original mediaeval Cornish text was heard on stage in the part of doubting Thomas.

The Legend of the Holy Rood

In medieval times, before the advent of the printing press developed in 1450 by Johannes Gutenburg and his first bible printed in Latin 5 years later, a number of popular myths and legends were circulating in Britain and in Europe among common folk. These legends were probably a way of making sense of some of the bible stories - in the same way as the Ordinalia trilogy presents bible stories in the vernacular.

One of these common myths is the story of the forbidden fruit in the garden of Eden. Nowhere in the Bible is there any description of this fruit, but the narrative sprang up that this fruit was an apple. Another embellishment of the traditional Bible story is the Legend of the Rood (or Holy Cross), which became a distinctive feature of the Ordinalia plays.

Not to be confused with The Dream of the Rood, an eighth century Old English Christian poem where the crucifixion story is told from the perspective of the Cross, the Legend of the Rood starts with the dying command of Adam to his son Seth, and ends with the cutting down of the tree used for the crucifixion of Christ.

The story goes that:

‘When Adam was dying, he sent his son Seth to the Gates of Paradise to beg the angel guarding them to give him the oil of mercy, to enable his father to live. The angel refused, but let him look at the wonders of Paradise, and gave him three seeds from the Tree of Life.

When Seth returned, he found that his father was already dead. So he laid the three seeds from the Tree of Life in his mouth, and buried him on Mount Moriah. With the passage of time the three seeds grew into three small trees. Abraham took some of the branches from the trees for the funeral pyre intended for the sacrifice of Isaac his son. At a later time, their branches were used for Moses’ rod, with which he struck the rock that produced the water to quench the thirst of his people.

Eventually the three trees grew together into one tree, which is believed to symbolise the mystery of the Holy Trinity. King David sat under its canopy when he composed the Miserere Psalm after he had confessed his sin with Bathsheba. Solomon cut down the tree to build the Temple on Mount Sion - but his workman could not cut it into any shape the fitted the purpose, and so Solomon angrily made them use it as a bridge over the brook of Cedron. After a while he buried it.

Over time, the remains of the tree became submerged under the Pool of Bethesda, famed for its healing powersIt was eventually found when it floated up to the surface of the pool was used as the Cross on which Christ died at Calvary.'

Our Ordinalia playwright has drawn upon this tradition in adapting the Ordinalia plays, and the narrative runs through all three plays in the trilogy as a unifying theme - as intended by the original author, a cleric at Glasney College in Penryn, which was a casualty of Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries.

One of these common myths is the story of the forbidden fruit in the garden of Eden. Nowhere in the Bible is there any description of this fruit, but the narrative sprang up that this fruit was an apple. Another embellishment of the traditional Bible story is the Legend of the Rood (or Holy Cross), which became a distinctive feature of the Ordinalia plays.

Not to be confused with The Dream of the Rood, an eighth century Old English Christian poem where the crucifixion story is told from the perspective of the Cross, the Legend of the Rood starts with the dying command of Adam to his son Seth, and ends with the cutting down of the tree used for the crucifixion of Christ.

The story goes that:

‘When Adam was dying, he sent his son Seth to the Gates of Paradise to beg the angel guarding them to give him the oil of mercy, to enable his father to live. The angel refused, but let him look at the wonders of Paradise, and gave him three seeds from the Tree of Life.

When Seth returned, he found that his father was already dead. So he laid the three seeds from the Tree of Life in his mouth, and buried him on Mount Moriah. With the passage of time the three seeds grew into three small trees. Abraham took some of the branches from the trees for the funeral pyre intended for the sacrifice of Isaac his son. At a later time, their branches were used for Moses’ rod, with which he struck the rock that produced the water to quench the thirst of his people.

Eventually the three trees grew together into one tree, which is believed to symbolise the mystery of the Holy Trinity. King David sat under its canopy when he composed the Miserere Psalm after he had confessed his sin with Bathsheba. Solomon cut down the tree to build the Temple on Mount Sion - but his workman could not cut it into any shape the fitted the purpose, and so Solomon angrily made them use it as a bridge over the brook of Cedron. After a while he buried it.

Over time, the remains of the tree became submerged under the Pool of Bethesda, famed for its healing powersIt was eventually found when it floated up to the surface of the pool was used as the Cross on which Christ died at Calvary.'

Our Ordinalia playwright has drawn upon this tradition in adapting the Ordinalia plays, and the narrative runs through all three plays in the trilogy as a unifying theme - as intended by the original author, a cleric at Glasney College in Penryn, which was a casualty of Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries.

Synopsis of the Plays

Origo Mundi (The Creation of the Earth)

The first play in the Ordinalia trilogy, this is the only Old Testament work. It sets the tone for the cycle - showing the Fall and the sinfulness of Man, interwoven with the story of the Cross, a symbol of redemption.

Taken from the book of Genesis, the story describes the relationship between God and Adam in the Garden of Eden, the temptation of Eve by the serpent Devil, and her tricking of Adam into eating the ‘forbidden fruit’. Expelled from Paradise for his sin, Adam wanders in the wilderness with his family. His son Cain kills his brother after an argument over the tithe (one-tenth portion) due to God. Adam then sends his third son Seth to seek out God and discover the ‘truth of the oil of mercy promised to him on the last day - a reference to the Christ child, by whose death all mankind will be saved.

The angel Gabriel gives Seth three seed pips from the Tree of Knowledge, and tells them to place them in Adam’s mouth on his death. One of the pips will become the tree that is used for the cross of Christ. After this momentous act, the plot turns towards the story of Noah, the building of the Ark and the Flood. And then shifts again to the story of Abraham and the intended sacrifice to God of his son Isaac. The next scene depicts the story of Moses and the burning bush, and his subsequent banishment with his people by Pharaoh out of Egypt - ending with the dramatic crossing of The Red Sea and the loss of the Egyptian army.

Finally, the action moves to King David whom the angel Gabriel commands to uproot the trees Moses had planted from the seed pips, and take them to Jerusalem. The abridged story tells of David sinning with Bathsheba, and being carried off to Hell by devils. His son Solomon then builds his famous temple ’to the glory of God’ and ordains a priest to become his Bishop to rule the temple. Egged on by Lucifer, the Bishop orders the execution of Maximilla (whose clothes spontaneously combusted - a sure sign of harlotry). The plays ends with the Bishop ordering the executioners to throw the trees planted from the seeds in Adam’s mouth, into the pool of Bathsheba.

Passio Christi (The Passion of Christ)

This second play in the trilogy is not so far ranging in scope. It covers the period of Christ’s life from his 40 days in the wilderness to his crucifixion and death. After his temptation by Satan, Jesus meets with his disciples and travels with them to Jerusalem for the Passover. Jesus expels from the temple there the merchants and consumers, accusing them of turning it into "a den of thieves”. The high priest Caiaphas sees this occur, and organises a plot to kill Jesus.

The subsequent scenes follow the true bible story more closely and in greater depth than the Origo Mundi. After the cleansing of the Temple, the plot follows the stories of Simon the Leper, Mary Magdalene and the annointing of the feet, the thirty pieces of silver, the Last Supper, Peter and the swords, and the betrayal by Judas.

The play reaches its climax with Christ on the Cross, and the torturers tormenting and mocking Christ before his death. Throughout these latter scenes is the figure of Pilate, responsible for the order to execute Christ and a precursor to the next play, the Resurrection - which opens with Pilate’s regret for his decision. The Passion lives up to his name, and its poignant last scene of Nicodemus taking and embalming the body of Christ is both dramatic and memorable.

The theme of the Rood story is continued in this play through the making of the cross, and the unusual (and rather Cornish) story of the Smith and the nails.

Resurrexio Domini (The Resurrection of Our Lord)

This last play has three clearly interlinked sections - the Resurrection, Pilate’s despair and the Ascension. It also is a sequel recalling the events of The Passion play. It tells of miracles - the freeing from prison of Nicodemus; the curing of Emperor Tiberius; Pilate protected by Christ’s robe. It delivers drama - the Harrowing of Hell and the release of the imprisoned souls; the reunion of Christ and his mother, Mary; the scenes at Christ’s tomb; and the triumphant ascension. And throughout there is the theme of Redemption - for those who see the play and believe its context.

The play opens in Pilate’s mansion with the affirmation of Christ’s death, and the accusations cast at Pilate by Nicodemus. Then moves to some comic and poignant scenes in Hell between Satan and his devils., and the powerful harrowing of Hell by God - with Jesus walking out of the mouth of Hell hand in hand with Adam. After returning to Hell, the scene shifts to the tomb and various reunions, and back to Pilate’s Palace as his guards tell him that Christ is alive. The apostles gather together at Galilee, and are eventually reunited with Jesus.

The scene with the healing of Tiberius through the sacred cloth of Veronica is clearly matched with the subsequent scene of Pilate protected by Christ’s robe, and his subsequent despair and suicide. There is then an immediate contrast with the shambolic scenes in Hell’s Mansion, and the comedy of the Executioners disposing of Pilate’s body in the Tiber. Finally the plot returns to its central themes of Redemption and the Ascension from the Mount of Olives, ending with Christ at the right hand of God.

The first play in the Ordinalia trilogy, this is the only Old Testament work. It sets the tone for the cycle - showing the Fall and the sinfulness of Man, interwoven with the story of the Cross, a symbol of redemption.

Taken from the book of Genesis, the story describes the relationship between God and Adam in the Garden of Eden, the temptation of Eve by the serpent Devil, and her tricking of Adam into eating the ‘forbidden fruit’. Expelled from Paradise for his sin, Adam wanders in the wilderness with his family. His son Cain kills his brother after an argument over the tithe (one-tenth portion) due to God. Adam then sends his third son Seth to seek out God and discover the ‘truth of the oil of mercy promised to him on the last day - a reference to the Christ child, by whose death all mankind will be saved.

The angel Gabriel gives Seth three seed pips from the Tree of Knowledge, and tells them to place them in Adam’s mouth on his death. One of the pips will become the tree that is used for the cross of Christ. After this momentous act, the plot turns towards the story of Noah, the building of the Ark and the Flood. And then shifts again to the story of Abraham and the intended sacrifice to God of his son Isaac. The next scene depicts the story of Moses and the burning bush, and his subsequent banishment with his people by Pharaoh out of Egypt - ending with the dramatic crossing of The Red Sea and the loss of the Egyptian army.

Finally, the action moves to King David whom the angel Gabriel commands to uproot the trees Moses had planted from the seed pips, and take them to Jerusalem. The abridged story tells of David sinning with Bathsheba, and being carried off to Hell by devils. His son Solomon then builds his famous temple ’to the glory of God’ and ordains a priest to become his Bishop to rule the temple. Egged on by Lucifer, the Bishop orders the execution of Maximilla (whose clothes spontaneously combusted - a sure sign of harlotry). The plays ends with the Bishop ordering the executioners to throw the trees planted from the seeds in Adam’s mouth, into the pool of Bathsheba.

Passio Christi (The Passion of Christ)

This second play in the trilogy is not so far ranging in scope. It covers the period of Christ’s life from his 40 days in the wilderness to his crucifixion and death. After his temptation by Satan, Jesus meets with his disciples and travels with them to Jerusalem for the Passover. Jesus expels from the temple there the merchants and consumers, accusing them of turning it into "a den of thieves”. The high priest Caiaphas sees this occur, and organises a plot to kill Jesus.

The subsequent scenes follow the true bible story more closely and in greater depth than the Origo Mundi. After the cleansing of the Temple, the plot follows the stories of Simon the Leper, Mary Magdalene and the annointing of the feet, the thirty pieces of silver, the Last Supper, Peter and the swords, and the betrayal by Judas.

The play reaches its climax with Christ on the Cross, and the torturers tormenting and mocking Christ before his death. Throughout these latter scenes is the figure of Pilate, responsible for the order to execute Christ and a precursor to the next play, the Resurrection - which opens with Pilate’s regret for his decision. The Passion lives up to his name, and its poignant last scene of Nicodemus taking and embalming the body of Christ is both dramatic and memorable.

The theme of the Rood story is continued in this play through the making of the cross, and the unusual (and rather Cornish) story of the Smith and the nails.

Resurrexio Domini (The Resurrection of Our Lord)

This last play has three clearly interlinked sections - the Resurrection, Pilate’s despair and the Ascension. It also is a sequel recalling the events of The Passion play. It tells of miracles - the freeing from prison of Nicodemus; the curing of Emperor Tiberius; Pilate protected by Christ’s robe. It delivers drama - the Harrowing of Hell and the release of the imprisoned souls; the reunion of Christ and his mother, Mary; the scenes at Christ’s tomb; and the triumphant ascension. And throughout there is the theme of Redemption - for those who see the play and believe its context.

The play opens in Pilate’s mansion with the affirmation of Christ’s death, and the accusations cast at Pilate by Nicodemus. Then moves to some comic and poignant scenes in Hell between Satan and his devils., and the powerful harrowing of Hell by God - with Jesus walking out of the mouth of Hell hand in hand with Adam. After returning to Hell, the scene shifts to the tomb and various reunions, and back to Pilate’s Palace as his guards tell him that Christ is alive. The apostles gather together at Galilee, and are eventually reunited with Jesus.

The scene with the healing of Tiberius through the sacred cloth of Veronica is clearly matched with the subsequent scene of Pilate protected by Christ’s robe, and his subsequent despair and suicide. There is then an immediate contrast with the shambolic scenes in Hell’s Mansion, and the comedy of the Executioners disposing of Pilate’s body in the Tiber. Finally the plot returns to its central themes of Redemption and the Ascension from the Mount of Olives, ending with Christ at the right hand of God.

The role of the Ordinalia plays in reviving the Cornish language

The Ordinalia plays constitute 3 out of the 5 surviving manuscripts of written Middle Cornish. According to different sources, they may pre-date or post-date the York Cycle of Mystery Plays - a cycle of 47 extant pageants or plays performed by the craft guilds of that city. They are believed to have been written in the second half of the 14th Century, after the devastation of the Black Death plague in 1349.

The opening words of the written text for the first play are 'Hic incipit Ordinale de Origo Mundi'. A free translation may be 'Here begins the script of the play Origin of the World.'

The text then continues in Medieval Cornish with Latin stage directions.

The Cornish Language was one of the six European Celtic languages, and was in the Brittonic Group comprising Breton and Welsh - although more closely linked to the former.

Cornish died out as a spoken language in the late eighteenth century, and much of our understanding of it comes from the Ordinalia plays. Apart from Old Cornish fragments in the Bodmin Manumissions, and some references in a Latin manuscript of Boethius, the only complete references are to be found in Middle Cornish manuscripts.

With the Ordinalia plays are the two other important records of the Cornish language - Beunans Meriasek, written around 1504, and Bewnans Ke, written around 1500, respectively commemorating the lives of the Saints Meriadoc and Kea.

Only three manuscripts of the Ordinalia remain, and with only two other extant manuscripts in written Cornish (lives of Cornish saints), they are a major source of understanding the Cornish language, which died out in 1777. The timeline for the revival of Kernewek after that can be found here

In 2009 UNESCO changed its classification of Cornish from "extinct" to "critically endangered” - a milestone for the revival of the language.

The opening words of the written text for the first play are 'Hic incipit Ordinale de Origo Mundi'. A free translation may be 'Here begins the script of the play Origin of the World.'

The text then continues in Medieval Cornish with Latin stage directions.

The Cornish Language was one of the six European Celtic languages, and was in the Brittonic Group comprising Breton and Welsh - although more closely linked to the former.

Cornish died out as a spoken language in the late eighteenth century, and much of our understanding of it comes from the Ordinalia plays. Apart from Old Cornish fragments in the Bodmin Manumissions, and some references in a Latin manuscript of Boethius, the only complete references are to be found in Middle Cornish manuscripts.

With the Ordinalia plays are the two other important records of the Cornish language - Beunans Meriasek, written around 1504, and Bewnans Ke, written around 1500, respectively commemorating the lives of the Saints Meriadoc and Kea.

Only three manuscripts of the Ordinalia remain, and with only two other extant manuscripts in written Cornish (lives of Cornish saints), they are a major source of understanding the Cornish language, which died out in 1777. The timeline for the revival of Kernewek after that can be found here

In 2009 UNESCO changed its classification of Cornish from "extinct" to "critically endangered” - a milestone for the revival of the language.

Resource Packs

Did you know?

1. The medieval Director of the plays was called the 'Ordinary', who was on stage directing the amateur actors, the majority of whom had not been taught to read. He carried the entire script, and acted as the prompter when lines were forgotten.

2.Glasney College was founded in 1265 at Penryn, a small village near Falmouth in Cornwall. Glasney was a centre of ecclesiastical power in medieval Cornwall and probably the best known and most important of Cornwall's religious institutions. It was dissolved by Henry VIII in 1548.

It was a college, or collegiate church, not an abbey (there were no monks there). It had an establishment of one provost and 12 secular canons and held the patronage of sixteen parishes., including that of St Just. Glasney College composed the Ordinalia trilogy, and another miracle play Bewnans Meriasek (the Life of St Meriasek).

3. A Plen an Gwari is an outdoor circular theatre for performing medieval drama in Cornwall. 'Plen an Gwari' survives as a name for two Cornish villages, one near Redruth and one near Goldsithney. There is also a village called 'Playing Place' near Truro. However, there are only two remaining surviving complete circular theatrical structures - one in St Just in Penwith, and the other at Perran Round, near Perranporth. The Plen an Gwari in St Just, a listed ancient monument, is now regularly used for theatrical performances and festivals and is believed to be the oldest working amphitheatre in Britain.

4. Pipers provided some of the music for the Ordinalia plays…There are references in two of the Ordinalia scripts to pipers '

Origo Mundi - Abarth an Tas, Menstral a ras, Pebough ware (In the name of the father, Minstrels of grace, pipe at once)

Passio - Mynstrels, gwreugh dhen-ny pyba' (Minstrels do ye pipe for us).

There is an example of Cornish pipes carved in the early sixteenth century on a bench end in Altarnun Church, Bodmin Moor. Other examples of carvings of Cornish pipes are in churches at nearby Davidstow, St Austell and Braddock,

The bagpipe shown has two long chanters of slightly different lengths with small bell ends. The chanters are fingered independently - one playing the upper half of the octave, the other the lower half.

2.Glasney College was founded in 1265 at Penryn, a small village near Falmouth in Cornwall. Glasney was a centre of ecclesiastical power in medieval Cornwall and probably the best known and most important of Cornwall's religious institutions. It was dissolved by Henry VIII in 1548.

It was a college, or collegiate church, not an abbey (there were no monks there). It had an establishment of one provost and 12 secular canons and held the patronage of sixteen parishes., including that of St Just. Glasney College composed the Ordinalia trilogy, and another miracle play Bewnans Meriasek (the Life of St Meriasek).

3. A Plen an Gwari is an outdoor circular theatre for performing medieval drama in Cornwall. 'Plen an Gwari' survives as a name for two Cornish villages, one near Redruth and one near Goldsithney. There is also a village called 'Playing Place' near Truro. However, there are only two remaining surviving complete circular theatrical structures - one in St Just in Penwith, and the other at Perran Round, near Perranporth. The Plen an Gwari in St Just, a listed ancient monument, is now regularly used for theatrical performances and festivals and is believed to be the oldest working amphitheatre in Britain.

4. Pipers provided some of the music for the Ordinalia plays…There are references in two of the Ordinalia scripts to pipers '

Origo Mundi - Abarth an Tas, Menstral a ras, Pebough ware (In the name of the father, Minstrels of grace, pipe at once)

Passio - Mynstrels, gwreugh dhen-ny pyba' (Minstrels do ye pipe for us).

There is an example of Cornish pipes carved in the early sixteenth century on a bench end in Altarnun Church, Bodmin Moor. Other examples of carvings of Cornish pipes are in churches at nearby Davidstow, St Austell and Braddock,

The bagpipe shown has two long chanters of slightly different lengths with small bell ends. The chanters are fingered independently - one playing the upper half of the octave, the other the lower half.

Our archive of the history of the Ordinalia, and their 2000-2004, and 2021 performances

This is accessible to schools, colleges and universities by appointment, and ranges across:

- the books, studies and materials used to research the context and settings of the plays;

- the history of the Plen an Gwari site;

- the development of the project and funding arrangements;

- the original and final scripts used for the performances;

- flyers and brochures for the productions, newspaper cuttings, and photographs of the cast, the sets, the costumes and the performances;

- cast lists, cue lists and rehearsal schedules; and

- the working diary of the director of the 2000-2004 performances, Dominic Knutton, after whom the building at the Knut was named.

Donations

Please consider making a small donation so we can make the St Just Ordinalia happen again! We are currently crowdfunding to do it in 2026 and it is a very large scale and ambitious project to achieve.

Donate Here

If you would like to make regular donations, please do so by signing up to direct debit on our Total Giving page.

With our thanks to everyone who helped realise our Ordinalia 2021 project - we are very grateful for your support.

Donate Here

If you would like to make regular donations, please do so by signing up to direct debit on our Total Giving page.

With our thanks to everyone who helped realise our Ordinalia 2021 project - we are very grateful for your support.

Contact Us

If you have questions, would like to support us, join the organising committee, or lend us your skills please email us on info(at)stjustordinalia.com

Postal communication can be sent to: The Knut St Just, Rear of 1-4 Market Street, St Just, Cornwall, TR19 7HX